Coverdale, from the start of the novel, has an odd way of telling his own story (in that he waffles on things frequently). The Blithedale Romance, which is told in first person perspective, lets us into the mind of Mr. Coverdale, giving what at first glance looks like a reliable viewing point. It doesn’t take long though, to see that Coverdale is not only an unreliable narrator for us, the audience, but doesn’t even seem to be sure what his own feelings are. (It’s no wonder we are often left confused by his narration.) There are many circumstances in which he behaves in an erratic and unpredictable manner, but I will be focusing on his (romantic) attractions to others.

We are introduced to his first love interest, Zenobia, not long into the novel. She is intriguing to him, and other, as he describes her as being like a “native” and a “queen” (13). Her pretty words praising his poetry only further lure him in, as he blushes and is filled “with excess of pleasure” (14). It is then that he deigns to eye-molest her, describing her in a near uncomfortable manner only the next page.

However, as mentioned before, he is unreliable and his affection easily bounces from person to person as even Hollingsworth was not safe from Coverdale’s amor. He describes Hollingsworth in such a way that could suggest homoerotic attraction to his friend, saying, “But there was something of a woman moulded into the great, stalwart frame of Hollingsworth; nor was he ashamed of it, as men often are of what is best in them, nor seemed ever to know that there was such a soft place in his heart” (42). All of this was thought while both lazed by a crackling fire, so much so, that it certainly sets a romantic scene.

Lastly (and bouncing very far ahead in the novel), we find out that (spoiler alert), apparently Priscilla was his romantic interest all along? His last confession, “essential to the full understanding of the story” was this (said while blushing), “I—I myself— was in love—with—Priscilla”(247). WHAT? All along? While entertaining thoughts of others?

In the span of less than 300 pages, Coverdale had bounced between three people romantically, and completely blindsided us at the end with his confession.

Perhaps the title is apropos in that it was ultimately a romance (no matter how mangled) and not necessarily about an attempt at living together in a utopia of sorts. Or perhaps, it was commentary on that idea of living in unison, that people can try to remove themselves from living “normally” as people in a city, but they cannot remove the fickle shallowness from inside themselves. Was Hawthorne saying that attempting to work together was a futile effort? We can only guess.

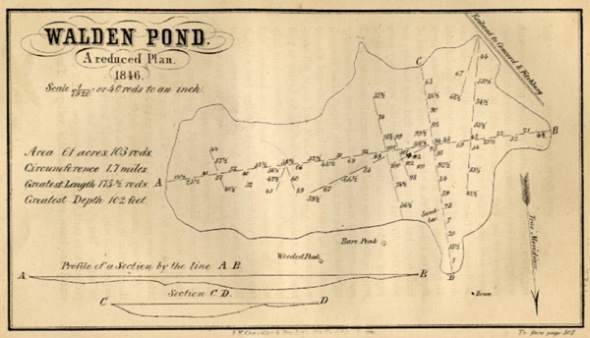

I think he juxtaposes them on purpose to say that he, and we (man) as a whole, need them to retain some balance and to find peace. When we spoke in class on the handout you gave (Emerson’s “Nature” vs. Thoreau’s, “Solitude”) I said that I felt the main difference between Emerson and Thoreau was that Emerson peeled away even his own skin to feel transcendence, while Thoreau experienced transcendence by not forgoing or ignoring the cycle of nature and how it affects us regardless of it being “material”. He believed that we should live humbly, and respectfully, not wasting any resources in our search for enlightenment. And I think that same idea shines through these two chapters.

In considering all sides (the animal vs. the spiritual) he is not wasting valuable resources and lessons he can glean from them. So, if he is truly living by his motto from his experiences at Walden pond, then these chapters are not as conflicting and contradictory as they first seem.

In “Higher Laws” on page 229 he says, “I found in myself, and still find, an instinct toward a higher, or as it is named, spiritual life, as do most men, and another toward a primitive rank and savage one, and I reverence them both.” Here it seems he is confirming my theory, in that he has found a balance and almost marriage of the two.

As far as “Brute Neighbors” is concerned, I almost would say he is metaphorically trying to describe the resilience and resistant of transcendence. It’s an unwieldy force that behaves as it pleases, it’s the little loon, inferior in intelligence than he but more cunning and swift than he. In “Brute Neighbors” on page 255 he says, “If I endeavored to overtake him in a boat, in order to see how he would manoeuvre(sic), he would dive and be completely lost, so that I did not discover him again, sometimes, till the latter part of the day. But I was more than a match for him on the surface. He commonly went off in rain.”

Certain key words clue me in to this, such as the use of the boat as a tool to overtake the loon. When someone tries to force transcendence through material tools, it’s a frustrating and fruitless experience. The transcendence would be lost until by chance later on when he wasn’t purposefully trying to take it by force. He also says that, “I was more than a match for him on the surface”, which says to me that he understands and can grasp what transcendence is at its most basic, and can even feel it… but that it isn’t the same kind of deep connection that people like Emerson feel. (Which I think also goes along with what he said in another passage, which I can’t rightly recall at the moment, but he said something along the lines of being only “charmed by nature”, but not being in rapture of it.)

And lastly, I think the last portion of that quote, “He commonly went off in rain.” is connecting to Emerson’s mentioning in previous writing that transcendence is based on the individual and whether or not they want to feel something. Again, my memory fails me. But I take the line metaphorically to mean, “When I’m in a bad place, I can’t even see hind nor tail of transcendence.”

Sorry for the long post!

Emerson’s Experience has a similar cadence to all of his previous writing. It has the confessional edge that both addresses an audience of some kind while also being a way for him to untangle his thoughts.

Experience starts out with a theme of trying and failing within only the first couple of pages. The amount of insecurity he feels bleeds through his writing with such sentences as “Where do we find ourselves?” or “If any of us knew what we were doing, or where we are going, then when we think we best know!” He wants to remain passionate but is struggling to find the drive and sense of wonder he once felt before the death of his son.

He shows this struggle and buckling in his beliefs when he downplays the idea of grief, saying, “The only thing grief has taught me is how shallow it is.” Which to me sounds as though he is arguing that being sad is fickle, even though by trying to suffocate it — he is undoubtedly only causing himself more emotional harm.

Cutting everything away (as Emerson is not a man of few words) Experience seems to be a way for him to work through his feelings over what has transpired. He needs vindication for the guilt he feels. Emerson seems to not only be mourning his son but also be mad at himself for mourning at all over something technically material. It goes against the Transcendentalist belief or being wholly self reliant. Not only was his son a source of happiness and wonder for him, but when his son was alive he was in a material body. The death of his son caused conflicting ideas inside of him, and crumbled the foundation of his Transcendentalist beliefs.

Within his final paragraph he says that we do everyday things like “dress our garden, eat our dinners…” and that these things make no real impression on us at the time but at the end of it all it’s what really matters when the ends of our lives draw near. Which, I think, is the most conflicting idea he’s ever presented. Because those moments are the here and now, and not the afterlife.

Divinity Hall: Site of Emerson’s Divinity School Address

I would have to agree with Robert D. Richardson that,”the opening sentence of the address is not a casual allusion to the weather or a clearing of the throat.” Instead, Richardson argues, “It is the central theological point of the talk.”

It is difficult to pick one or two allusions that Emerson hides in his writing to discuss today. Certainly, his description of the weather is not simply a description of the weather. There is deeper meaning. First, he reminds us of the wonder we can feel for Nature. Emerson describes it with such a visceral sense that the reader/listener feels enchanted. He uses the senses to seduce and lull his audience into a false sense of security. The “grass grows”, “buds burst”, and “stars pour”. What a day to be alive! He describes the world as though it is ripe for the picking and ready and willing to be enjoyed by any man should he but reach out and grasp it… and I do believe that is one of his main points. As in much of his writing, he aims to not only stew over and organize his own ponderings, but encourage all like minded individuals to do the same. Even if he does it in a more abstract way than others.

Next, he gives the metaphor of man (man kind) as a child in comparison to the vastness of nature, and the world as his toy. The innocence isn’t so innocent. He is showing us that we are ignorant and naive until our eyes have been opened to the possibility of a spiritual awakening (he hints at this with certain key words like “mystery” in reference to nature, going as far to describe rays as being something spiritual all the while never once having mentioned the idea of “God”). He paints nature as something holy and sacred, but readily at man’s dispense. A strange parallel, when once again we find ourselves talking about something fairly abstract.

“…and also how you think the first paragraph generally relates to the rest of the address. Was he trying to make his audience uncomfortable right from the start?” You ask me.

I’m not sure I feel that his aim is ever to make his audience purposefully uncomfortable so much as aggressively thoughtful. Emerson was very passionate about his way of thinking, and converting through what he considered rationalism, all those willing to listen to him (though some, like those listening to his address, were more of a captive audience). Not far into his address he says, “Behold these infinite relations, so like, so unlike; many, yet one. I would study, I would know, I would admire forever. These works of thought have been the entertainments of the human spirit in all ages.” Emerson may not have believed in the traditional concept of the Christian God but he believed the human spirit or, the soul, existed. He felt like he was close to unlocking the secret to life, to being, and likely was hoping that by targeting future preachers that somehow he would be inspiring likeminded individuals to chase after the same dream he chased his entire life. And maybe, in inspiring them, that they would find that missing piece that so eluded him despite his fervent belief in transcendentalism.

Henry David Thoreau. Walden Pond. A reduced Plan. 1846, plate in Thoreau’s Walden: or, Life in the Woods (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854).

I think it’s obvious that Thoreau has a kind of reverence for nature. He even gets to a point in his own life where he believes it’s a good idea to divest himself of (most of) his worldly possessions and live alone for two years in the woods on a lake. That certainly says something, doesn’t it?

I’m not sure I’d go as far as to say he’s promoting going green or environmentalism. I think it is a coincidence that they are looking a little too heavily into. His writing strikes me as more of published introspection. I absolutely adore his one line, from page 2; “I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well.” That line hooked me immediately. It was very honest. Personal experiences and personal opinions make excellent fodder for writers. Thoreau was a deep thinker, someone who wasn’t satisfied with simple answers. He wanted to look beneath the underneath and writing was an excellent outlet to record his thoughts and expand on them.

On page 7 he shows his dissatisfaction with modern man’s lifestyle and critiques it, saying, “…it appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there is no choice left.” It is such a jolting and relatable thought. And it’s terribly fascinating to me because it ties into a project I’m actually doing right now for one of my art classes, Three-Dimensional Design.

My classmates and I were given a handout on finding inspiration, for our next assignment. The handout was an excerpt from an article written by Linda Weintraub. I wont go into crazy detail but one of the artists she sited was Scott Greiger. Scott Greiger is an interesting fellow because he started out studying anthropology and shifted into the arts later on. However, he gleaned what he learned studying indigenous peoples and rural situations and used it as inspiration in the kind of art he made. He was quoted as saying,

“Anthropology is here and now. This was new information. Corporations assign values with out our permission: ‘Anything that creates profit is good.’ I am against vocabulary of corporatization. For all the claims of diversity and enriched environment, my feeling as an anthropologist is that there is less choice today than historically. You are required to adapt your activities and thinking to what is available… If a CEO or president or general doesn’t like something, the course of thousands of lives change. I believe change actually comes from the thoughts of many individuals.”

I find it fascinating that two men separated so vastly by time, circumstances and history can have such perfectly aligned thoughts. If anything, I think both men would have something to say about how blindly the average man goes about his life robotically and in a blur. I think that’s why Thoreau liked nature so much; it made him feel human. It wasn’t something contrived by man.

I will conclude this blog post now by saying that I believe it wasn’t about how we treat the land, but what the person got out of working the land. In raising the beans, Thoreau was allotted a lot of time to think to himself. He matured and developed. He was a different person when he came out the other side.

Using only one of the two stories as evidence, discuss how you think Hawthorne or Poe reveals the “dark” side of human perception. Put another way, how might the story you choose serve as a critique of Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” moment, where perception leads to spiritual transcendence? What does perception lead to for Poe and Hawthorne?

Let me just begin this new blog entry by saying, reading “The Fall of the House of Usher” is not a good story to read late at night. When you are alone in your room. I wont be making that mistake twice.

Also, I’d like to give a disclaimer. I’m going to try not to seem stilted in my opinion (is that possible?) or judgmental. What I write is merely observation and speculation on my part. The last class we had felt more like a philosophy debate than American Literature Survey and if I wasn’t comfortable discussing it in class, I’m surely not comfortable discussing this sort of thing online either…

Poe definitely is dark. I feel like Poe has a way of skirting issues and around the way he sees the world. Poe reveals the dark side of human perception by making his audience uncomfortable. Perhaps it is his desire to make the reader as uncomfortable with these issues as he is. Tackling issues like death, and depression and anxiety, etc. He tested the boundaries of his beliefs with his writing. He also had a way of writing symbolically, which, while being an ongoing religious theme, seems to fit nicely with the transcendentalism movement. An example would be the scene at the end of this short story, where moonlight shines through the fissure in the family home. Or even the fissure itself.

I’m not good at understanding hidden meanings in writing; I’m more of an Ernest Hemingway kind of girl. Complex ideas usually throw me. So, do I think “The Fall of the House of Usher” serves as a critique of Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” moment? I don’t know. I don’t think so. Poe’s writing to me has always seemed cathartic. “There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart…” Sometimes when I read Poe’s work I feel like an intruder. It seems very personal. Like he’s deciding who he is and what he believes with every line he writes.

If he was being purposefully critical of Emerson, I missed it. I think it’s impossible to not insert a part of yourself into your writing. This is something my British Literature 1660 to Present class discussed. Everyone has a way of subtly inserting their own beliefs and ideas into their writing. Nothing is unbiased. I would also argue that the “transparent eyeball” moment, where perception leads to spiritual transcendence is a bit formulaic in story telling. The “Ah-ha!” moment isn’t reserved for introspective thinkers.

Now. Emerson is something else entirely. He is very direct when he talks about his beliefs. He may describe them in (long and drawn out) poetical ways, but he manages to be very direct with the reader. It’s something I’ve actually come to appreciate.

Though they had different writing styles and different approaches to deciding what they believed in, I think they would both agree that language cheapens the human spirit*. It’s not enough and it will never be enough to articulate the full depth of human nature.

*Quote taken from classmate.

I was honestly fooled when I first watched this movie. It’s amazing to think the apartments in the movie are all hand crafted and on set! It was a movie worth watching and I would recommend it to anyone. Now, on to my blog post:

I visualize the window as a mirror when I watch this movie. The mirror is a means of reflection as to what is going on around you (and in you). Jeff is wheelchair bound and has no means of entertainment and succumbs to nosily peeping on neighbors. I would think inner reflection is normal during times of high stress. With his broken leg, he’s more likely to question his abilities and see his limitations more clearly. It visibly strains his relationship too. Almost like a cascading affect. He seems to see a permanent relationship with his girlfriend as a handicap.

Lisa doesn’t help either; she’s got to leave to go work (reminding him of his solitude and inability to travel) and nags him to change careers.

However, there’s definitely something to be said about finding love in the “midst of tragedy” as Jeff and Lisa do. Ironically it seems a murder, (certainly the most nefarious of all sins) is what keeps them together. The end of the film even reveals Lisa considering Jeff’s feelings by spending more time with him and taking interest in things he likes (well, at least while he is awake) by reading a book on foreign travel.

To me, all the other neighbors are different fragments of Jeff and Lisa as a couple. They are insights into an alternate universe for them. The composer sets the tempo and mood and rhythm. I don’t necessarily see him as a shade of them so much as a prop to help move the story along. (The dramatic background music for instance.)

I see Mr. and Mrs. Thorwald as Jeff and Lisa at their absolute possible worst. They are a caricature of what could happen to them should they follow on the path they are on at the start of the movie — bitter and bickering.

The newlyweds also seem to be a caricature, sweet and loving to each other at first, they showcase the ideal relationship. Which dissolves quickly, perhaps as a lesson from Hitchcock. It seems to serve as a warning that relationships require a consistent and determined effort to love your other half. (Familiarity breeds contempt?) It is interesting that the husband continually opens the window and once his wife notices, begins to fuss at him for it. I also believe this can be seen as a sign of reflection — and his wife does not like him thinking heavily on it.

Fairfield Porter: Painting Materials ca. 1949 oil on canvas

I am both a writer and an artist. And I seem to be drawn to anything relating to the two. There’s a sense of comfort and familiarity that I feel when I see art supplies. The possibilities are endless. There’s a potential to create something the world has never seen before, straight from your mind. There’s a feeling of peace when I hold a paintbrush in my hand or smell fresh oils squeezed onto a pallet… it’s indescribable. There aren’t enough words in the English language.

This painting has so much potential. I don’t think anyone would have to think long on something to write about. The arrangement of the art supplies, though dissonant and scattered is well balanced. The color scheme is warm, and though the scale of colors isn’t very broad, works in favor of the painting as a whole. A poet could compare the warmth of the picture to the lack of human presence. The items seem to be left alone, and untouched for sometime. Does that have anything to do with how many brushes there are in the painting? What are they all used for? What is casting the shadows?

Once someone starts questioning the “why”s and “how”s, they can easily come up with an imagined answer for themselves. It’s only a matter of organizing your thoughts on paper.

My thoughts are Marrow in my mind.

Who held these brushes?

Who left them behind?

They are— Forgotten.

I decided to address two of the three blog questions proposed. I hope that is okay. It’s always hard to touch on just one issue. Especially when I feel the two I chose are connected.

“Discuss Mamet’s use of profanity in the play. Is there a reason for it, or is it merely gratuitous?”

I expected the constant use of “vulgar” speech to offend me. However, the warning I received prepared me for the worst that would never come. Words are words. I assume Mamet’s use of profanity was both for shock-value and emphasis. I feel (especially after both reading the play and comparing it to a movie clip) that the words rapidly lost their value. I became desensitized very quickly. I suppose one could argue Mamet even intended for my reaction, implying that even the characters had become desensitized to their situation, to what they did and to why it was wrong.

That brings me to the second brain tickler, “Toward the end of the play Roma tells Levene that “it’s not a world of men,” and earlier Moss reassures Aaranow that “we’re men here, George.” What does it mean to be a “man” in this world? Are some characters more “manly” than others? And finally, what is Mamet’s attitude toward his characters?”

All the posturing in the play was overwhelmingly caricaturized. It would have been an absolute shame for such a scenario to have actually taken place. Similar to the constant use of profanity, I grew desensitized to their yelling and attempts at gaining some measure of control over one another.

When Roma tells Levene, “it’s not a world of men” I think he is referring to what he considers a real man. Roma is willing to go above and beyond what is morally corrupt to make sure a deal doesn’t fall through. He puts himself on a pedestal and has divorced any morals from his life. He has a warped image of what a man is.

I’m not sure what constitutes being manly. The first things that come to my mind are beards and Lumber Jacks. That doesn’t help me answer the question at all though, so let’s use the stereotype of timidity as an indicator of non-manliness.

Aaronow’s tendency to be mousy and his lack of drive will then sufficiently make him eligible for the un-manliest man of the year award. As pathetic a creature as he is in the play he possesses the “best” morals. If Mamet hadn’t ended his play with “The Machine” getting caught, I’d almost assuredly tell you his theme was “nice guys finish last”. In the end it seemed he was the only one that came out unscathed (not including his wounded pride at being questioned by the cops and the insinuation of being guilty).

Mamet’s attitude toward his characters is extremely negative. I can’t even pretend to understand why he wrote the play the way he did. I can only hypothesize he was trying to make a point. He villainized co-worker competition, authority, and the idea of what a “real man” should be. I have too many different theories to touch on. If anything, Mamet did a very good job of creating believably flawed men who honestly thought they were living their lives the way they should have been, right or wrong.

“King Lear and the Fool in the Storm” by William Dyce

I’m annoyed greatly by the excerpts from Coppelia Kahn’s essay. I will try to not let her opinions color mine as thoroughly as it has ruffled my feathers!

I must say it took me very little time to find offense in Kahn’s writing. The title in and of itself was upsetting. But the explanation of the title, “Kahn argues that Lear’s transformation over the course of the play involves his gradual understanding of–to put it bluntly–the woman in himself” made me even more upset.

Let me start by saying I’ve never heard of anything more ridiculous in my life. To imply that Lear was changed by the blossoming of his inner woman is an incredible lie. There are no excerpts of any kind (that come to mind, mind you) that gives that synopsis any weight in the text.

I must also impress upon you, the reader, to negate the statement “…when applied to a play from the early seventeenth century–that Lear must learn to welcome those “women’s waterdrops,” the tears that he is so afraid to shed, along with a more “feminine” kind of power whose source is the emotional life,” referring to the above quote about Lear’s inner femme. I do not believe a play from the early seventeenth century, which was performed by people who possess poetic license in interpreting Shakespeare’s work, should carry any kind of weight in Kahn’s argument. If we are critically analyzing the character Lear, we should analyze the original Lear from the original text. I would also like to point out that tears are not strictly feminine. To say otherwise is sexist. I digress. During the time King Lear would have taken place such an act was considered strictly feminine, but a modern essayist has no excuse.

“But what the play depicts, of course, is the failure of that presence: the failure of a father’s power to command love in a patriarchal world and the emotional penalty he pays for wielding power.” Kahn argues. (I find it strange she finds that King Lear’s time was sexist but doesn’t recognize her own sexism.) She certainly villainizes the idea of holding power here too. In Act one both Kent and Cordelia attempt to use their power for the betterment of the King. Where Cordelia sasses Lear, whom she actually loves, and Kent defends her plainness of speech from Lear. Even the Fool, throughout the play uses his “power” (his seeming immunity of the King’s wrath) to reach out to Lear. One such notable scene being in Act one, Scene four where the fool subtly coaxes Lear into saying “nothing can come from nothing” mirroring the scene where Lear casts out Cordelia. It was a risky move on his part, but the Fool pulled it off. A similar scene is in Act three where King Lear bares himself to the storm that reflects the storm he is feeling inside. The Fool is quick to gain seriousness and speak sense to Lear.

I speak with experience when I say King Lear is not embracing his inner female. Such a notion belittles and ignores the very real pain that Lear was experiencing. He lived his whole life with a status that demanded respect and was shocked when people did not maintain his fantasy world after he stepped down from his title. He was blissfully unaware of how he wronged people with his selfishness. Would his hysteria not be a natural reaction? My father and I used to fight a lot. We had bitter fights that lasted for weeks. I empathize with King Lear’s character because it is a grossly skewed caricature of my own father. I am a caricature of Cordelia. There is a sense of helplessness in feeling your children do not respect you and honor you. A lack of communication on both ends can bring each party to absolute madness. In Act two, Scene four immediately after Regan and Goneril turn their father away, King Lear says he will go mad. It is my opinion that he means, with grief. While Kahn may continue to argue that King’s decay into madness is a product of understanding a feminine presence in his psyche, I maintain that it is grief in losing all control over his life.